|

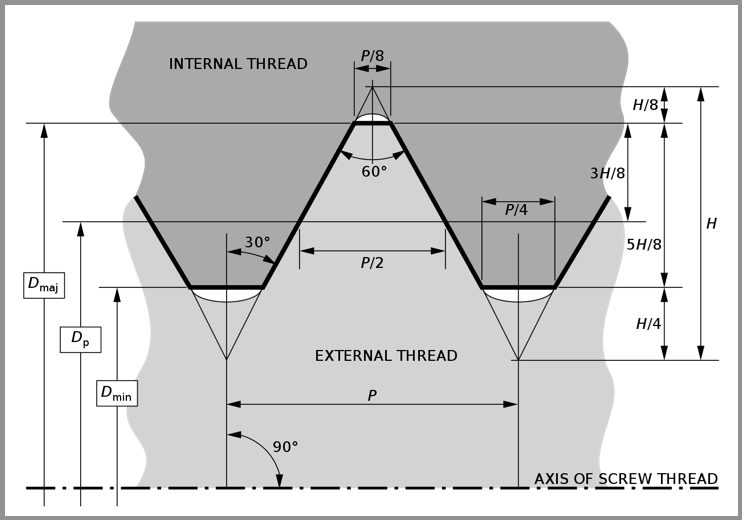

written, compiled and edited by Bernard Martin Class of fit for a cutting tap refers to the specific tolerance or fit that is desired between the threads of the tap and the threads of the hole it is being used to create. In other words, it defines how tightly or loosely the threads should mesh together. The class of fit is typically expressed using a combination of letters and numbers. The most commonly used standards for class of fit are the Unified Thread Standard (UTS) and the ISO metric thread standard. In the UTS, the class of fit is denoted by a combination of a letter and a number, such as 2B, 3A, etc. In the ISO metric thread standard, it is represented by a combination of a letter and a number, such as 6g, 4h, etc. For cutting taps, the class of fit is usually specified based on the intended application and the level of precision required. The class of fit can affect factors like the ease of assembly, the strength of the threaded connection, and the ability to engage the threads smoothly during tapping. A classification system exists for ease of manufacture and interchangeability of fabricated threaded items. Most, but certainly not all, threaded items are made to a UTS classification standard. This system is analogous to the fits used with assembled parts.

The letter suffix "A" or "B" denotes whether the threads are external or internal, respectively. Classes 1A, 2A, 3A apply to external threads; Classes 1B, 2B, 3B apply to internal threads Here are some common classes of fit for cutting taps:

The standard designation for a UTS thread is a number indicating the nominal (major) diameter of the thread, followed by the pitch measured in threads per inch. For diameters smaller than 1⁄4 inch, the diameter is indicated by an integer number defined in the standard; for all other diameters, the inch figure is given.

This number pair is optionally followed by the letters UNC, UNF or UNEF (Unified) if the diameter-pitch combination is from the coarse, fine, or extra fineseries, and may also be followed by a tolerance class. Example: #6-32 UNC 2B (major diameter: 0.1380 inch, pitch: 32 tpi)

0 Comments

Technical article courtesy of Regal Cutting Tools Most craftspeople will agree that whenever an internal thread can be made with a roll form tap, this is the tool that should be used for the job. Roll taps, also known as form taps, hold distinct advantages over cut taps. Roll tap advantages are inherent in the way they create the threads. As the names suggest, these taps form the threads by rolling and deforming the material inside the hole. They push the metal out of the way to create the thread roots and base. Cut taps, also true to their name, carve metal away from inside the hole, ejecting chips as they go. Reasons to Use Roll Form TapsRoll taps are a great option when considering workmanship and price point. First, roll taps are chipless. Because they do not remove material from the hole, form taps generate no chips that must be removed. This carries several advantages:

When Not to Use Roll TapsWhile an excellent choice for most applications, there are a few situations that do not lend themselves to roll tapping including:

Types of Roll TapsRoll taps are engineered and manufactured in two main styles to match the type of hole and fastener to be used. Bottoming roll taps feature little to no taper on their end threads. This allows full thread production to the very bottom of the hole.

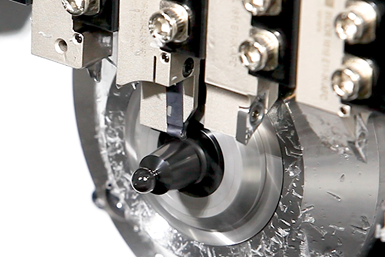

The bottom 3 to 5 threads on a plug tap are tapered to allow the tap to gradually begin deforming the hole material, creating less stress on the tool and giving the full threading edges a base from which to work. Regal Cutting Tools has built a reputation for high quality taps and other metalworking tools and an uncompromising commitment to customer service. Regal manufactures a full line of roll taps to suit any application. Regal can even engineer custom taps quickly and affordably. To learn more about Regal’s taps and learn which products are best suited for your workflow, contact our team today. Appears in Print at Production Machining as: 'A Swift Tool Change for Swiss-Type Machines' This coolant-through tooling system replacement for the gang plate on a Swiss-type machine can save hours of spindle downtime per day as well as increase tool life and enhance chip control. While servicing the tools on a traditional platen on a sliding headstock lathe, it can take 10 minutes or more to index one insert. While indexing the tools, coolant spigots can get knocked loose by an operator and can cost a machine shop tool life and time. Once the inserts are indexed, it can take several starts and stops of the spindle for the operator to see if the coolant stream is being directed to where it needs to be.

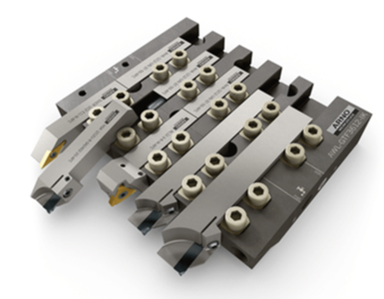

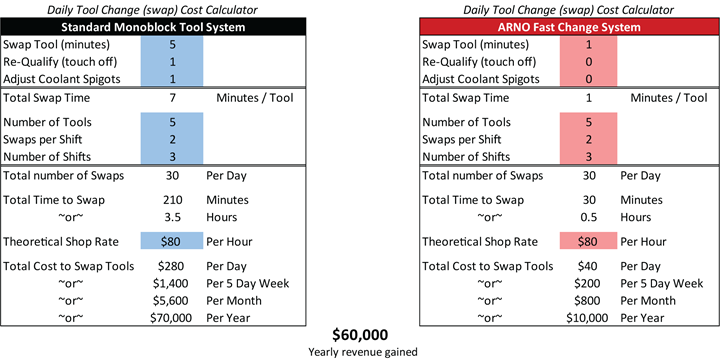

Arno’s Fast Change (AFC) tooling system consists of a gang plate that holds split-shank, coolant-through turning tools, parting tools and grooving tools. Designed like a manifold, the coolant is rerouted through the gang plate to the tools. The UN-style slot in the fixed stop picks up the coolant and runs it through the pipette to the front end where the coolant goes directly to the cutting edge. The AFC system can supply coolant to one port that supports all the tooling positions, or it can supply two ports and divide the tooling positions with the needle valve. The tooling system only needs to be plumbed once and, according to the company, after that, a high-pressure coolant line should not need to be touched again. With proper setup, the high-pressure lines are moved behind the machine guards, creating a clean machining environment. This enables operators to complete safer routine maintenance. Also, the AFC’s low-profile clamps do not collect as many chips compared with a typical clamping system. When replacing a split-shank tool, the operator simply loosens two clamps to remove the cutting head and then replaces it with a new one, the company says. Simple, Quick FunctionalityA Time and Money SaverUsing the AFC system, Arno reports that it takes 17 seconds to change a tool, a vast improvement to the typical 7 to 10 minutes it can take using a traditional gang plate. The conventional method might take five minutes to change a tool, a minute to touch the tool off and another minute to adjust the spigot, for instance.

In comparison, when an operator is working with the AFC system, retouch is not necessary because the tool will repeat within plus or minus a thousandth of the previous tool positions. There is also no need to factor in time for readjusting coolant lines because the new system is a true, coolant-through system. It is also not necessary to factor in the clearing away of chips because those surfaces have mostly been eliminated with the smooth AFC design, according to Stroup. Therefore, the 17-second tool change time is the only time to factor in. But, for a real-world example, he increases the time to one minute to consider a distracted operator that might use extra seconds Although there are still 30 idle times per day, there are now only 30 minutes of downtime per day instead of 210 minutes using the traditional gang plate. “That only costs $10,000 per year, which means you’ve just made $60,000 a year on that one spindle by adopting the AFC system,” Stroup says. Almost a year ago, Allen Benjamin, which has been a part of North American Tool, was purchased by GWS Tool Group. GWS Tool Group is a US-based, vertically integrated manufacturer of highly engineered custom, standard, and modified standard cutting tools, primarily servicing the aerospace and defense, power generation, automotive and medical sectors. GWS Tool Group has acquired multiple businesses in the course of its growth which now serves as the respective manufacturing divisions for the Company.

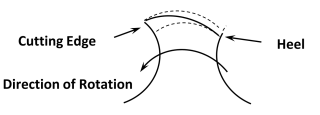

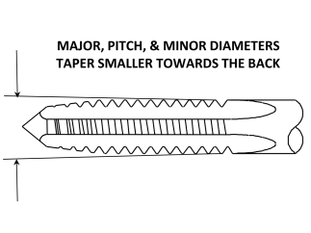

Just because there is a new owner, doesn't mean that the quality of an Allen Benjamin Tap has changed! If you’re in the market for high tensile strength carbide taps and metric taps, we can assure you that you’re in the right place. Not only is Allen Benjamin a leading supplier of the industry’s most durable, longest lasting carbide taps, we offer our customers the convenience of ordering online. In this day and age, we believe that quick access and top-notch customer services are critical. In today’s post, we’re going to look at why it is beneficial to order your carbide taps from Allen Benjamin. Quality Allen Benjamin carbide taps are highly efficient when tapping abrasive metals such as aluminum, non-ferrous metals, and exotic materials. With a much higher tensile strength than standard taps, their high-quality carbide taps can withstand the rigorous demands of your application. Selection Allen Benjamin offers a staggering range of carbide taps, metric taps, HSSE taps, tapping fluid, extensions, and more. If it’s taps that you are looking for, you can be confident that they’ve got them and have them ready for delivery. Service Allen Benjamin guarantees that all of their products will be the absolute best quality, within standard tolerances and dimensions, and consistent with application specifications. If their goods don’t meet your needs, you can contact us for a return authorization. At Allen Benjamin, they take pride in offering the industry’s best taps. But, more importantly, they aim to provide our customers with access to a simpler, faster way to order their operation’s critical parts, supplies, and components. If you’ve been searching for a supplier that will meet your needs and rise to meet your challenges contact us today! Have you ever had a tapping job that was so troublesome that it caused heartburn or acid indigestion due to broken taps, bad finish, short tap life, over or undersized threads, etc.? One way of avoiding or alleviating such a condition is accomplished with the use of a tap feature called “relief”. The definition of “relief” according to Marian Webster, is removal or lightening of something oppressive, painful, or distressing. For a tap, “relief” is the reducing of surface contact between the tap/tap feature and the part being tapped. Surface contact generates unwanted heat causing the issues mentioned above. Depending on the tap feature, relief is applied in a direction that is, radially, around the tap, or axially, along the axis of the tap. All taps require a minimum number of features to have relief for it to cut, other reliefs are applied when the tapping application requires it. There are always tradeoffs when designing a tap, if a relief is applied or it’s amount is greater than necessary, it can cause the tap to run free or loose to a point it will cause heartburn or acid indigestion by producing issues mentioned above. Relieved features that are always necessary on a tap are: Chamfer, the tapered threads at the front of the tap. The crests or major diameter of the chamfered threads are radially relieved from the cutting edge to the heel of the land. Without this relief it would be like cutting a tomato with the non-sharp side of a knife, you can imagine the results of that. When looking at a taps chamfer, relief results in the crest width being wider at the cutting edge and narrowing towards the heel; Back Taper, a slight gradual reduction of the taps thread form including it’s major, pitch and minor diameters. It starts at the chamfered end of the tap and continues axially for the length of thread towards the shank end.

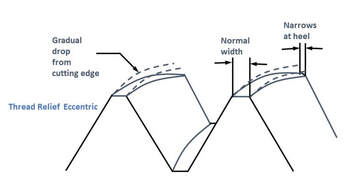

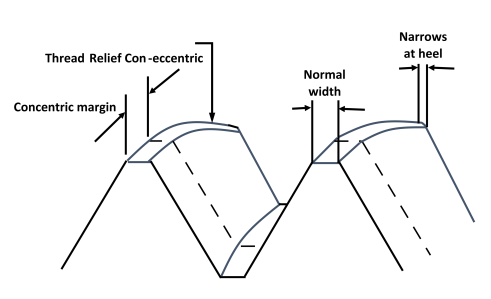

Additional features that can be relieved Thread Relief, a radial reduction of the taps major and pitch diameters from the cutting edge to the heel. Relieving of the pitch diameter results in the minor diameter being relieved as well due to the manufacturing process whereas the major diameter is relieved separately. The application of the major or pitch diameter relief is normally applied separately but both can be done in combination. Relief of pitch diameter is the most common followed by the major diameter. Thread relief is applied when Back Taper alone is not enough to prevent surface contact when tapping materials that close in and squeezes the tap like stainless steel. The rate of reduction from the cutting edge to the heel is based on the material being tapped and, in some cases, the tapping application. There are two common types of Thread Reliefs:

The reliefs we have discussed so far are applied during the tap manufacturing and other than the chamfer relief cannot be added or changed. If you are in a bind and must ship parts but can’t wait for us to design, manufacture and ship the appropriate tap, there are additional types of relief that can be applied that may work in a pinch. Sometimes referred to as a poor man’s relief, something you may be capable of doing in your shop without too much trouble to get you through a quick job, or until properly designed tools arrive. The application of relief types and amounts are dependent on many factors such as material properties being tapped, style and size of tap, how the tap is being used (hand, machine, etc.) and application requirements, etc. By providing us with as much information about your tapping application, it will enable our engineers to design a tap with the proper relief. This will help alleviate troublesome heartburn or acid indigestion. Edit January 2024: Changed banner image

The Dümmel Minimill-System with three or six cutting edges is the next big thing for ultra groove milling and threading machining from 0mm to a 32mm bore diameter. The indexable carbide heads are screwed on with three ribs coupling. This guarantees the best possible rotation and repeatable accuracy. A large selection of standard inserts as well as toolholders from steel and carbide are available from stock. With six cutting tools available, there's sure to be one that you can use to generate higher feed rates, longer tool life with higher stock removal rates. The six cutting edged Minimill-system is also available with an anti-vibration carbide toolholder or a steel tool holder. North American Tool realizes how confusing the painstaking math is to get preplate part limits and a Tap “H” limit, but don’t worry, all you have to do is contact us with your thread information, and we will do the work. Call us at 800-USA-TAPS. If you want to know how it's done, we’ve included the formulas for the engineer in all of us. If you want to know how it’s done, we’ve included the formulas for the engineer in all of us. When encountering an internal threaded hole requiring it to be plated, it normally needs to be produced oversize to accommodate the plating. There are two methods for determining the correct Tap “H” limit, the “Detailed Method” and the “Simplified Method”. The “Detailed Method” requires you to do more math, but it will also determine the before plate product limits (GO & NOGO) The “Simplified Method” requires less math but will not provide you with the before plate product limits (GO & NOGO) When the plating is applied to the properly oversized threaded hole, the required thread class (2B, 3B) or special PD (pitch diameter) will be met. The effect of plating on a 60° screw thread is a change in PD of 4 times the plating thickness (2 times on each side). That is because the plating itself is parallel to the thread flanks, and the PD is measured perpendicular to the thread axis. As an example, a .0002 plating thickness X 4 results in a PD increase of .0008 (The ratio of 4:1 is for 60° threads only, the ratio for other thread forms such as ACME, 29° is different.) Detailed MethodBefore determining the tap size (H limit), it is necessary to determine the oversize part thread limits first. Once this is achieved, the tap limit is normally position at 40% of the before plate limits. Unfortunately, life is not always easy. The required plating thickness on the print, purchase order, etc. will be expressed in one of two ways, a “Maximum and Minimum Thickness” or a “One Value Thickness” requiring two different ways to calculate the oversize part thread limits. Maximum and Minimum Plating Thickness 1. The Minimum part PD (pitch diameter) is larger by 4 X the Maximum plating thickness 2. The Maximum part PD (pitch diameter) is larger by 4 x the Minimum plating thickness 3. The Tap “H” = a PD that is located at 40% of the before plate limits – minimum after plate limit \ .0005 (“H” limit increment). Selecting the closes “H” limit Example: 1/4-20 UNC-2B, plating thickness, .0002 to .0003 (1/4-20 UNC-2B after plate PD = .2175 – .2224) 1. GO Minimum before coating part PD (pitch diameter) =.2175 (after plate GO or minimum PD) + .0012 (4 X .0003 max plating thickness) = .2187 2. NOGO Maximum before coating part PD (pitch diameter) = .2224 (after plate NOGO or maximum PD) + .0008 (4 X .0002 min plating thickness) = .2232 3. Tap ‘H” Limit .2232 (Maximum before coating part PD) – .2187 (Minimum before coating part PD) = .0045 .0045 X 40% = .0018 .0018 + 2187 (Minimum before coating part PD) = .2205 .2205 (before plate Tap PD) – .2175 (after plate or minimum PD) = .003 0.003 / .0005 (“H” limit increment) = H6 One Value Plating Thickness When a “One Value Plating Thickness” is shown, we establish a maximum and minimum plating thickness values to compute the maximum and minimum before platting thread limits. This is done by assuming that the tolerance on the plating is 50% larger than the “One Value Plating Thickness.” The maximum plating thickness is 6 X, the “One Value Plating Thickness,” and the minimum plating thickness is the same as the “One Value Plating Thickness.” 1. The Minimum part PD (pitch diameter) is larger by 6 X the “One Value Plating Thickness” 2. The Maximum part PD (pitch diameter) is larger by 4 x the “One Value Plating Thickness” 3. The Tap “H” = a PD that is located at 40% of the before plate limits – minimum after plate limit \ .0005 (“H” limit increment). Selecting the closes “H” limit Example: 1/4-20 UNC-2B, plating thickness, .0003 (1/4-20 UNC-2B after plate PD = .2175 – .2224) 1. GO Minimum before coating part PD (pitch diameter) =.2175 (after plate GO or minimum PD) + .0018 (6 X .0003 “One Value Plating Thickness”) = .2193 2. NOGO Maximum before coating part PD (pitch diameter) = .2224 (after plate NOGO or maximum PD) + .0012 (4 X .0003 “One Value Plating Thickness”) = .2236 3. Tap ‘H” Limit .2236 (Maximum before coating part PD) – .2193 (Minimum before coating part PD) = .0043 .0043 X 40% = .00172 .00172 + .2193 (Minimum before coating part PD) = .2210 .2210 (before plate Tap PD) – .2175 (after plate or minimum PD) = .0035 0.0035 / .0005 (“H” limit increment) = H7 Simplified MethodThis method requires knowing what tap “H” limit that is recommended for the thread class of fit (2B 3B etc.) after plating.

Example: The recommended “H” limit for a 1/4 – 20 UNC 2B would be GH5 and for a 3B it would be GH3. Maximum and Minimum Plating Thickness When the plating thickness requirement is given with a maximum and minimum limit you would simply, Example: 1/4-20 UNC-2B, plating thickness, .0002 to .0003 (1/4-20 UNC-2B after plate recommended “H” limit GH5) One Value Plating Thickness When the plating thickness requirement is given with a one value plating thickness limit you would simply, Multiply the plating thickness by 4 (the 60° size change ratio) to determine the PD (pitch diameter) size change in inches. Then divide the PD size change in inches by .0005 (“H” limit increment). The result would be the increase in “H” limit and added to the recommended “H” limit for the required after plate thread class. Example: 1/4-20 UNC-2B, plating thickness, .0003 (1/4-20 UNC-2B after plate recommended “H” limit GH5) .0003 X 4 = .0012 (PD size change in inches) .0012 / .0005 = 2.4 (PD size change in “H” limits) rounder to the closest “H” limit = 2 Recommended “H” limit of GH5 (recommended “H” limit for Class 2B) + 2 = GH7 (pre-plate “H” limit) Arno Werkzeuge USA has reintroduced the H.B. Rouse brand of American-made carbide cutting tools and inserts.  Arno Werkzeuge USA has reintroduced the H.B. Rouse brand of carbide cutting tools and inserts. Formerly sold and marketed under the Arno-Rouse name, the company has reintroduced Rouse as a standalone product offering a broad range of carbide boring bars, tools and inserts for manual turning operations. The carbide insert turning tools have triple-sided inserts for quick change turning operations. Triple-tip boring bars offer an improved triangular insert located within a precision-machined pocket to eliminate shifting under heavy cuts; the insert requires the simple removal of one screw for indexing. Boring bars feature carbide inserts that provide three cutting edges instead of only one (as is common with brazed-tip tooling). |

AuthorWe've compiled the latest news and technical information about our principals and our market that we hope you find informative! Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Browne & Co., Inc.

9605 Tanager Drive Chardon, Ohio 44024 |

© 2024 Browne & Co., Inc. All Rights Reserved

web design by Rapid Production Marketing |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed